I adored this week’s reading on weiqi, liubo, and Chinese playing cards. They were all unique in their own way but what stuck out to me was weiqi. Now I know that we are going more in-depth with weiqi next week but I have been fascinated with weiqi, I knew it as go and thought it originated in Japan, since I was in elementary school. I was introduced to the game by manga, anime, and my sister. My sister use to be a part of a Japanese emersion camp every summer in Minnesota, this was when we lived in the lower 48. She was heavily influenced from this camp and I was as well as I looked up to my sister and always tried to do what she did. We bought a go set that had a simple wooden board and tiny plastic tiles and it was very confusing at first. Reading about weiqi brought back memories of frustration and long hours of just staring at a board playing against myself. It was a game of strategy, patience, and intelligence not just in how you are going to move but what your moves say about you. I am still horrible at weiqi but it is one of my favorite board games to date.

The Art of Contest reading on weiqi was nifty because it gave us the history of the game and the players, men and women. It was similar to when I was first discovering the history of how Islam spread in my high school history classes because reading it just made me want to research weiqi more so I could truly understand the game I fell in love with so long ago. Weiqi’s need for strategy as it is “both the simplicity and the complexity of the game…” (Chen, 643). There are a seemingly endless amounts of combinations of moves and play with weiqi, go, and baduk. It is like trying to catch an eel in water as once you think you have a good solid strategy it slips away once an opponent finds and exploits your weaknesses. It is a game that forces you to not only be predictable but spontaneous and wild at the same time. Without that essence of spontaneity the player will lose game after game to players who have used this unpredictability regularly. Then there is the art within this war like game.

The reflection of not only one’s self but of humanity is an abstract but heavily written upon subject of weiqi. I remember doing this reflection when I was playing against myself. As I looked down at my pieces I saw that I was very aggressive, predictable, and impulsive on where I placed my pieces. As I was a high school student at the time I looked back on what I had done up until then and realized that I acted like that in everyday life. The Upper class of pre-modern China reflected on themselves as well and also on how the game represents humanity. Reading Zu-Yan Chen’s work I found a poem that I really enjoyed by Liu Yü-his, “First, I perceived dotted stars in the dawn sky; / Then, I saw soldiers fighting in late autumn./ Your deployment was as wild geese in flight—nobody understood it,/ Until the cub was caught in the tiger’s den, and all were shocked.” (Chen, 646) I liked this couplet because it showed me a beauty of weiqi at attracted me. There are other poems with the same eloquence but was captured me was the beauty and brutality on the game captured in these four story lines. Maybe I am just rambling a little but I feel affection for most things that involve poetry and self-reflection.

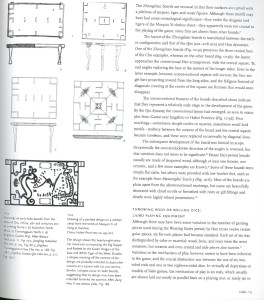

The image that I was interested in the most was Liubo board diagram d on page 115 from the Art of Contest. The reason I chose this picture is because, as we have discussed in class and the Art of Contest reiterated, we have no idea on how to play this game the way it was meant to be played. We have all of these boards, diagrams, pieces, and knowledge from some anecdotes but we cannot seem to piece together this puzzle that has stumped many people. In a way that makes it fun and beguiling to read and learn about what we do know about this game called liubo.

Chen, Zu-Yan. “The Art of Black and White: Wei-ch’i in Chinese Poetry.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 117.4 (1997). Print.