“I finally filled my pokedex!” I remember telling my grandfather sometime in 1998.

“What the hell is a pokedex?” he responded to my abject horror.

The act of collecting Pokemon is an interesting experience for multiple reasons; like Baseball Cards in the 80s and Pogs in the 90s, Pokemon were a manifestation of the strange cultural trend towards pop culture collectibles with one key difference: None of them were real or tangible. The act of filling a Pokedex was a feat of almost herculean strength on the playground, and if you had done it people would clamor around your gameboy like it was a font of information on every possible detail about Pokemon life. By capturing all 151 Pokemon you became somewhat of a cultural librarian, curating details and providing a library of both knowledge and cultural power to those who understood just how amazing it was that you had caught all of them. What we didn’t realize at the time was just how bizarre this was to, well, pretty much everyone.

In Iwabuchi’s How Japanese is Pokemon, Pokemon are considered to be culturally coded material. Like Sushi or Chopsticks, Pokemon are perceived globally to be a uniquely Japanese thing (regardless of whether or not this is inherently true). Whether or not you agree with this, or see the western influences in Pokemon designs or backstories, to consume Pokemon is in some way willingly giving yourself temporarily to the powerhouse of Japanese media. The thing is, it’s rare for something so culturally defined to provide such a sense of ownership to its participants. Regardless of where you’re from or how much you love the games the Squirtle you picked at the beginning belonged to you, god dammit, and no one could take that away. Even as you traded them and trained them they would only listen to you if you had certain parts of the game completed. To Gamefreak this was a means of implementing progress gates so that people could not break their games, but this also implied a certain power over the act of catching and curating your museum of creatures. In many ways, the game itself — whether it be the trading cards or the video game — was literally designed around the control of found objects.

The act of catching Pokemon or obtaining cards was somewhat arcane and strange. One had to scavenge near-empty store racks and trade with friends to get new cards. In the case of the game, one needed to find a friend with the opposing color-coded copy of the game to trade and capture every kind of Pokemon as the versions had different sets of monsters. This provided two distinct rewards to the player: One would gain the ability to use the Pokemon and their unique abilities in Battle, and one could read more information about them on the bottom of the card (or in the case of the game, in the pokedex). Pokemon commodified otherwise arbitrary knowledge about its intangible and fundamentally unreal creatures so well that people actually began stealing cards. Children lined up at their TVs in the morning to watch the extremely popular TV show and play Who’s That Pokemon between commercial breaks. These things have become so ingrained in American cultural memory that as participants we forget that what we’re doing is essentially studying.

Iwabuchi’s position that Pokemon are global but still “smell” of Japan is powerful in its implication that it, to the fears of many parents, indoctrinated children in what was essentially Japan’s media export. I say this out of a sense of love and somewhat bewilderment towards the subject matter but I mean no harm; Pokemon is sort of amazing in its ability to push children to dig and study and learn. Pokemon is, in a sense, archaeology. Its roots are buried deep within Japan and the Japanese market, slowly disseminated through time into other regions and unpacked and examined with excruciating detail by the masses of global children that couldn’t get enough of Pikachu and friends. And while Pikachu may have been constant throughout, the localizations and global markets have reacted to, taxonomized, and embraced different Pokemon differently.

In 1000 years when our descendants dig up the landfills packed with Pokemon cards and old game carts I’m not entirely convinced they’ll understand the importance of our long lost civilization of monster cultivation. But I know that in the world we live in now, I can trust that everyone understands what it means to fill a Pokedex.

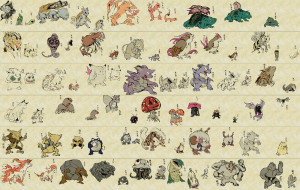

Pokehyaku, by Asamegraph

Slider image by Asamegraph.