The idea of the apocalypse is a concept that is ingrained in the human imagination. Early human writings and religious texts centered around the concept of the end of the world. In more modern times, the concept of the apocalypse became less of an abstract idea, to be inflicted upon the world at some point by a divine being, and more of a real, tangible concern. The development and stockpile of nuclear weapons, as well as the ever-expanding capacity to deliver them anywhere and everywhere on the globe, forced the people of the world to face the very real possibility that the end would come, and it would be a product of our own doing and not a result of an external force.

This modern apocalypse has been the basis for many different pieces of media and is a favorite setting for games in particular. Nuclear annihilation is a common trope on both sides of the Cold War, with the US and Eastern Bloc countries both adapting the concept to reflect their own fears and cultural issues. The geopolitical strife that gave rise to the popularization of the nuclear apocalypse is an almost universal concept, but the interpretation of global nuclear war and its aftermath is distinctly shaped by the view through the respective cultural lenses of the game’s creator or creators.

Two modern games embody the application of the apocalypse, each created around the same time and on different sides of the globe. Metro 2033, and its sequel Metro Last Light, were developed by 4A Games in Kiev, Ukraine in 2010 and 2013 respectively.1 Fallout 3, on the other hand, was released in 2008 by the American game studio Bethesda Softworks out of Maryland.2 Each title deals with a world that has been destroyed by atomic war and focuses on how the inhabitants of different areas deal with the aftermath, but the execution of the game, its feel and themes, are wildly different despite their cosmetic similarities.

Fallout 3 takes place in the Capitol Wasteland, the remains of Washington DC and the larger DC metro area. The game world is a sprawling expanse of land, ranging from the city of DC to the largely eradicated suburbs and countryside beyond. The game itself is non linear; the world can be tackled in almost any order the player chooses. An extensive selection of items such as clothing and weapons can be found throughout the world for the player to loot, sell or ignore.3 The player experience is incredibly varied, with most of the wasteland consisting of exploration, light combat and item management, though some missions have far more intense and taxing demands placed upon the player.

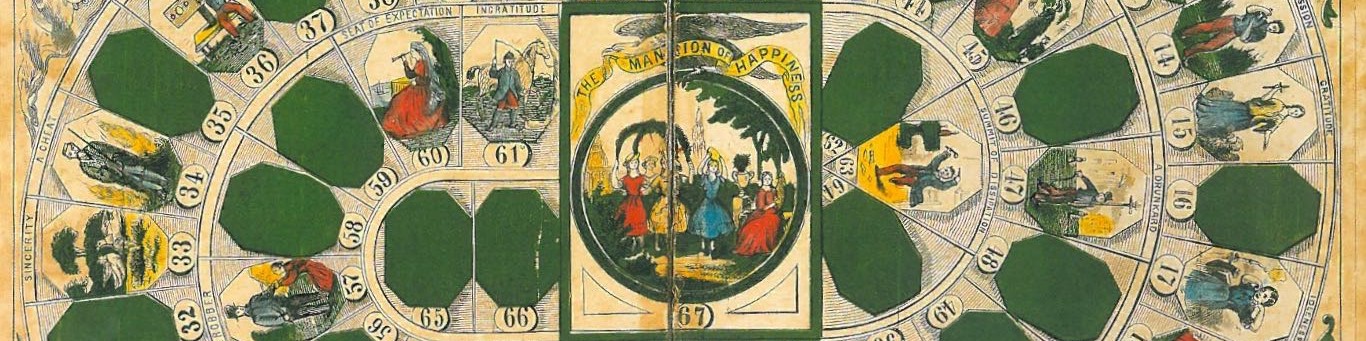

The Capitol Wasteland, Fallout 3

The Metro series is in a very similar vein to Fallout, in that it deals with people surviving in the ruins of civilization. Metro takes place on the other side of the earth, in a bifurcated world with the subways and tunnels below Moscow occupying half the game and the frozen, irradiated and monster infested surface composing the other. The player must navigate the world, working through the metro and the abandoned city in an effort to find military aid for his home station.4 Metro is a far more constrained affair, with encounters occurring in a more linear order. Where Fallout offers the player with a vast expanse of play area, Metro confines the player, moving them down a single story and path.

A Metro Station, Metro 2033

While Metro might have a more constrained game world, the layout and design of both games communicate a sense of the culture that gave birth to the game. Fallout centers around American urban and suburban culture. Much of the game world takes place in the vacant ruins of track homes and cities, each complete with couches and TVs, all rotting and useless. Once the game releases you onto the surface, the first place the player ends up is a small town called Springvale. This town, in the game, consists of a handful of houses, a gas station and a school.5 It is a town that could be found anywhere in the US, albeit one that has been bombed, abandoned and decaying for years.

Springvale is contrasted by an occupied settlement to the north called Megaton. Springvale is an untouched relic of before the apocalypse, whereas Megaton is a thriving community built from the pieces of that pre apocalypse world, though assembled in the post apocalypse.6 Megaton is a shantytown, a city made of scraps of metal, buses, cars and planes all moved and assembled around the crater of an atomic bomb. It is a place of the apocalypse, a reassembly of pre war objects, as opposed to an application of a singular pre war item, like the metro.

Metro’s world has a similar theme of reuse and reconstruction. The world is organized on two primary axes, the first being the layout of the metro itself. The metro, both in the game and in reality, is a system of nodes or stations connected by tunnels. In the game each station is a settlement. Some are abandoned, some have grown up in the years after the bombs, but they are the core units of life. The game goes out of its way to give each station its own character and qualities, with each one being its own city with its own government.

The second axis that the game world is oriented on is one of the dichotomy between the subterranean inhabited world and the abandoned surface. Above ground is a ruined and frozen Moscow, occupied by mutated creatures and monsters and deadly radiation. The only way of surviving above is to be heavily armed and to bring a gas mask with plenty of filters. The surface is dotted with relics of the older Soviet order. Generic locations such as apartment buildings and stores can be found along side more recognizable structures such as Red Square, Saint Basil’s Cathedral and the Kremlin.

The frozen surface of Moscow, Metro 2033

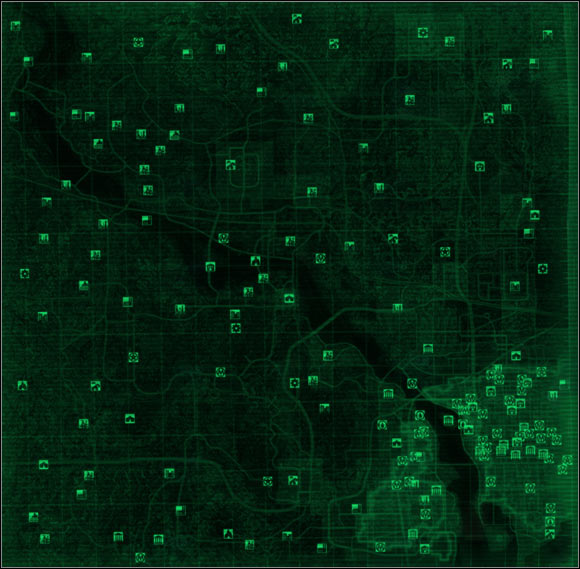

The structure of the subway system and Moscow at large is a reflection of the concept of a “center/periphery binary” that was in place in the Soviet Union.7 This idea was tied with the concept of Communism, the idea of top down control. For the Soviet government, “greatness radiated from the center.”8 This conceptual and physical idea of the center is visible in the radial nature of Moscow, and by extension its subway system. Moscow, during its reconstruction in the 1930’s, was recast in this concentric mold and was designed to be a “socialist showcase capital.”

Metro system map, Metro 2033

In the years after the fall of the USSR in 1991, this central core was seen as rotten, but the concept of power radiating out still remained ingrained in the Russian psyche. Metro 2033 specifically touches on this in the journey of the main character Artyom and his goal of reaching the center of the metro system, a station called Polis, in an effort to raise reinforcements for the defense of Artyom’s home station.9 Artyom literally journeys from the periphery to the center in hopes of salvation, yet when he arrives, there is none to be found. He instead must journey to the surface and solve his own problems, either through force or diplomacy.

This thematic emphasis on the center does not exist within Fallout. The world is more chaotic, with towns, settlements, forts and cities all placed haphazardly and evenly across the game world. There is also no central power; out of the most powerful factions, they are aligned by good and evil, not inept. The leaders of Polis in the metro have the power to act, but do not because of their own failings. In Fallout, each faction is either acting to the best of their abilities, pushing forward with an almost single-minded zeal, or they are shackled by external forces that are lifted by the player character through the course of the game.

The Capitol Wasteland map, Fallout 3

This interplay between power, agency and geography shows a distinct divide between Fallout and Metro and reflects their national origins. Fallout is marked by urban and sub urban sprawl, a relatable and common mark of American life. Metro, on the other hand, shows the control of the state and the center, and the disenchantment with the ultimate product of that center. Virtue in both Metro and Fallout is found in the self, but Fallout has a much greater emphasis on organizations. Factions in Metro are shackled by ineptitude, in Fallout external forces constrain them.

Another point of both similarity and cultural divergence is the role of the military in both games. The military, combat and military arms play a huge role in both titles, but the militaristic culture comes through far more in Metro. Fallout is a more abstracted universe, with both the world and its factions being stylized and distorted through a fictional lens of 1950’s aesthetic.10 Military hardware and weapons are fictionalized, for example the Assault Rifle in-game is an amalgamation of several real world weapons and is named for its function, not with any specific, even fake designation. The uniforms as well are generic and stylized. There is a distinct degree of separation between the game’s world and the real world.

Assault Rifle from Fallout 3. Can you name this weapon?

Metro lacks the abstraction. It contains a relative proximity to the subject at hand through a realistic portrayal of materials, location and people.11 Weapons are either realistic representations of real weapons or are plausible home-made weapons from after the apocalypse. The armor is made of period Russian gear that, while modified and haphazardly assembled, is still recognizable for its original state. Beyond this, military hardware is explicitly required to progress in the game and to survive. Gas masks allow the player to live in areas that would normally kill a person, such as the irradiated surface and certain tunnels choked with toxic gas. Fallout has no such requirement; the game can be completed with almost no intervention of force or military gear. Metro makes the military a core part of the game and of the world, even if the military that the equipment was created for no longer exists.

Assault Rifle from Metro 2033. This one you could name though.

This deep link with the military ties back to the historical and modern roots of Soviet society. In Metro, the military, as represented through its equipment, is a life saving tool, be it the medical kit, the gas mask or the player’s rifle. The military history of the former Soviet Bloc is reused and applied in a positive light, moving from the totalitarian past to a life saving, yet post-apocalyptic future. It is an almost fetishizing the military, while at the same time a condemnation. The ending of the game, which involves the deployment of nuclear missiles, is a thing that can be averted through careful player action. The military can save, but it is not a solution to everything. This resonates with modern Russians in that, in the words of the games writer, Russians still feel “problems of survival.”12

In the Western tradition, Fallout keeps the military question at arm’s length. Killing is almost always vilified and the gear has no grounding in reality. It places the violence at arm’s length, wrapping it in a fictional world in a way that Metro does not. Metro uses its proximity to the subject material to make a point and to project a viewpoint, something that Fallout does not. Metro strikes closer to home for modern Russians, reflecting a sense of fear of the world.13

Both Metro and Fallout use a morality system that guides the game experience and player actions. While fundamentally similar in the goal of rewarding player behavior, both morality systems operate in very different manners. In Fallout, the moral system is straight forward, both in how it is communicated to the player and how it is used in the game. From the beginning the game informs you that there are “good” and “bad” dialogue options, with the specific choices labeled as such. In addition, player actions that garner good or bad “karma,” as it is called in-game, invoke an on-screen response showing the result of the action and the status of your karma can be checked any time through the game menus.14 The result of your karma level effects many outcomes of the game, both in how the game portrays you upon conclusion, as well as what people follow you and who you can interact with.

Metro takes a different course in its execution of its morality system. The system itself is almost completely transparent, the only feedback relating to your actions is a slight sound and lightening of the screen. The game does nothing to convey what actions result in any change in morality and never even mentions the existence of a moral system at all.15 In addition the moral points are obtained in a more oblique way than in Fallout, with players being awarded points for completing tasks that would be conventionally thought as moral, such as giving money to poor children, as well as gaining points for completing more unusual tasks, such as exploring the world, listening to people’s every day conversations and finding caches of gear scattered off the beaten path.16 Many of these acts would not be thought as traditionally “moral” but still yield moral points.

The conclusions reached through the obtaining of moral points in Metro is equally ambiguous. The game has two primary endings, both which deal with how to solve the problem of the sentient mutants attacking stations throughout the metro. In the ending, labeled the Ranger ending, where the player ignores the moral points, the military organization that the player enlists the help of upon his arrival at the central Polis station helps the player launch nuclear missiles to eradicate the mutants. In the Enlightened ending, on the other hand, the player comes to the realization that the mutants might not be evil and allows the player the choice to abort the missile launch.

Metro’s moral system has three main aspects that set it apart from Fallout’s Karma system. The first is its obtuseness. Fallout communicates the intent, cause and effects of its karma system, while Metro does no such thing. Second, Metro rewards not just “moral” actions but actions that are self enriching. Exploring the environment is not good or bad, but contributes to the player and the player character’s emotional growth and understanding of the world. Metro does not have a moral system so much as it has a personal growth system.

Finally, while the “bad ending” in Metro offers no choice as to what happens, the “good” ending allows the player to choose. The same final result as the bad ending can still be achieved in the good one, the player is not given a good ending so much as they are given agency at that specific moment. Fallout simply tallies the points gained and checks them when determining what happens with a player. While sometimes the player can override the result of their karma, the singular occasion of choice shown in Metro becomes far more important, where as Fallout is riddled with choices; one more or less means very little in the over all theme of the game.

These specific differences stem from the origins of each game. Fallout derives its morality system from older tabletop RPGs, using a system called SPECIAL to decide the outcome of various skill checks, karma being just one.17 Morality is just another skill, another number to be manipulated in the game. Metro’s choice comes from a deeper cultural source. The idea of education leading to choice also ties into the earlier concept of the “center/periphery binary” and the fall of the Soviet Union.

Exploration and education allow for player agency. The corrupt center found in Polis, the organization that is unable to help the player because of internal strife and failing, pushes the player character to fire the nuclear missiles at the mutants. It is through understanding the world that this corrupt influence of the center is prevented.18 This has many similarities to rule under the USSR. The central government dictated what was to happen, as well as controlling the opinions around a person. It was a totalitarian state in which a person had little to no agency. It was only through individual actions, exploration of the world around you and questioning people near you that personal agency could be achieved. The good ending of Metro does not force the good outcome on you, instead it allows you to make the choice for yourself.

Fallout 3 and Metro 2033 each have their roots in the cultures that gave birth to them. The “cultural odor” clings to each piece and informs not just their aesthetic design, but their deeper gameplay structures and methods of engagement with the player. The “cultural odor” or deep seated cultural thumbprint has been impressed on each title in a way that indelibly marks them as either Russian or America.19 If you were to take Metro 2033 and change the setting and characters into a European fairy tale, the journey the character takes and the choices that are forced upon them reflect the common history of the Soviet Union and all its satellite states. That common history acts as a universal touchstone for that particular people and creates a distinct feel that sets Metro 2033 apart from Fallout 3.

1 “Metro 2033 (video Game).” Wikipedia. Accessed May 8, 2015.

2 “Fallout 3.” Wikipedia. Accessed May 8, 2015.

3 Bethesda Game Studios (Developer). “Fallout 3.” Video Game. Bethesda Softworks. 2008.

4 4A Games (Developer). “Metro 2033,” Video Game. Deep Silver/THQ. 2010

5 Bethesda Game Studios (Developer). “Fallout 3.” Video Game. Bethesda Softworks. 2008.

6 Bethesda Game Studios (Developer). “Fallout 3.” Video Game. Bethesda Softworks. 2008.

7 Mark Griffiths, “Moscow after the Apocalypse,” Slavic Review, Vol. 72, No. 3 (FALL 2013), pp. 481-504

8 Mark Griffiths, “Moscow after the Apocalypse,” Slavic Review, Vol. 72, No. 3 (FALL 2013), pp. 481-504

9 4A Games (Developer). “Metro 2033,” Video Game. Deep Silver/THQ. 2010

10 Bethesda Game Studios (Developer). “Fallout 3.” Video Game. Bethesda Softworks. 2008.

11 Natalia Sokolova, “Co-oplting Transmedia Consumers: User Content as Entertainment or “Free Labour”? The Cases of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Metro 2033,” Europe-Asia Studies Vol. 64, No.8 (2012) 1565-1583

12 Natalia Sokolova, “Co-oplting Transmedia Consumers: User Content as Entertainment or “Free Labour”? The Cases of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Metro 2033,” Europe-Asia Studies Vol. 64, No.8 (2012) 1565-1583

13 Ulrich Schmid, “Post-Apocalypse, Intermediality and Social Distrust in Russian Pop Culture,” Russian Analytical Digest 126 (2013) 2-5

14 Bethesda Game Studios (Developer). “Fallout 3.” Video Game. Bethesda Softworks. 2008.

15 4A Games (Developer). “Metro 2033,” Video Game. Deep Silver/THQ. 2010

16 “Moral Points.” Metro Wiki. Accessed May 8, 2015.

17 “SPECIAL.” Fallout Wiki. Accessed May 8, 2015.

18 “Moral Points.” Metro Wiki. Accessed May 8, 2015.

19 Tobin, Joseph Jay. Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Bibliography

Natalia Sokolova, “Co-oplting Transmedia Consumers: User Content as Entertainment or “Free Labour”? The Cases of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Metro 2033,” Europe-Asia Studies Vol. 64, No.8 (2012) 1565-1583

Ulrich Schmid, “Post-Apocalypse, Intermediality and Social Distrust in Russian Pop Culture,” Russian Analytical Digest 126 (2013) 2-5

Mark Griffiths, “Moscow after the Apocalypse,” Slavic Review, Vol. 72, No. 3 (FALL 2013), pp. 481-504

Tobin, Joseph Jay. Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Bethesda Game Studios (Developer). “Fallout 3.” Video Game. Bethesda Softworks. 2008.

4A Games (Developer). “Metro 2033,” Video Game. Deep Silver/THQ. 2010

“SPECIAL.” Fallout Wiki. Accessed May 8, 2015.

“Fallout 3.” Wikipedia. Accessed May 8, 2015.

“Metro 2033 (video Game).” Wikipedia. Accessed May 8, 2015.

“Moral Points.” Metro Wiki. Accessed May 8, 2015.