In October 1949 an independent minor league American baseball team, the San Francisco Seals, embarked on a goodwill tour in Japan. The tour, whose mission was to contribute to the building of goodwill between the United States and Japan, and to help revive baseball in Japan after its prohibition during the Second World War, was not the first of its kind, and it would not be the last. However, this particular tour had another unique purpose: fighting communism. It was the height of the second Red Scare and McCarthyism in the United States, and Japan seemed to be in a particularly precarious position. It was geographically nestled between the epicenter of communism at the time, the Soviet Union, and newly communist China, where the People’s Republic had been proclaimed just weeks before the arrival of the Seals. At least one San Francisco coach, Del Young, thought the tour played a significant role in stymying communism in Japan: “When we got there the Communists were on the soap boxes on almost every street corner. But we hadn’t been there long before they disappeared in the crowds.”[1]

In October 1949 an independent minor league American baseball team, the San Francisco Seals, embarked on a goodwill tour in Japan. The tour, whose mission was to contribute to the building of goodwill between the United States and Japan, and to help revive baseball in Japan after its prohibition during the Second World War, was not the first of its kind, and it would not be the last. However, this particular tour had another unique purpose: fighting communism. It was the height of the second Red Scare and McCarthyism in the United States, and Japan seemed to be in a particularly precarious position. It was geographically nestled between the epicenter of communism at the time, the Soviet Union, and newly communist China, where the People’s Republic had been proclaimed just weeks before the arrival of the Seals. At least one San Francisco coach, Del Young, thought the tour played a significant role in stymying communism in Japan: “When we got there the Communists were on the soap boxes on almost every street corner. But we hadn’t been there long before they disappeared in the crowds.”[1]

When I began researching for this project, I loosely planned on examining baseball’s function as a tool for American imperialism in East Asia around the early part of the twentieth century. This is a story that has already been told, though, both through baseball specifically and sport more generally. We read Brownell’s Training the Body for China this semester, which touches on this aspect of sport on a few occasions. Given the lack of English language primary sources from the era, and my own inability to read non-English sources, it seemed like I would only be able to rehash what other people have already written. Baseball’s connection to anti-communism in the Cold War era, however, seems to be less well known. This connection existed in both domestic and foreign affairs. In this piece, I’ll look at both spheres. The aforementioned tour of Japan by the San Francisco Seals provides an example of the use of baseball as an anti-communism tool abroad, and Jackie Robinson’s breaking of the color barrier and his subsequent House Un-American Activities Committee testimony. To be sure, I am still largely restating what other scholars have already said, but I hope to connect two seemingly disparate stories into one narrative––baseball as an anti-communist tool––that itself is less prominent than other narratives dealing with baseball’s role in American, and global, history.

From its earliest days, baseball has been linked to American society and values. The game’s imagery has been almost infinitely malleable. It has been connected to the professionalization of American society as well as to early twentieth century trends like immigration, industrialization, and urbanization. Some scholars have argued it served as a means to convey “American values” such as “hard work, social mobility, democracy, and teamwork.”[2] This was no different in the post-World War II era, when “baseball was also viewed as a means by which American values might be extended into the third world to gain new friends in the ideological struggle with communism.”[3]

Proponents of anti-communism and domino theories felt they needed such a friend in Japan. It was Douglas MacArthur, staunch anti-communist and avid baseball fan, who called on Seals manager Lefty O’Doul to arrange the Seals’ tour to Japan. It was MacArthur, too, who overrode objections to the tour from some American politicians, who saw the staging of competitive games between “an American professional team and Japanese teams implying equality, regarded by some U.S. officials as not appropriate during the occupation.”[4]

The Seals arrived in Tokyo on October 13, 1949, and the rousing reception they immediately received was an indicator of what was to follow. Thousands of fans greeted them at the airport and along their motorcade route. Thousands more attended the games, including then crown prince Akihito. One instance of Akihito shaking hands with O’Doul provided “a perfect opportunity to portray visually a new phase in U.S.-Japanese relations.” Furthermore, the Japanese public was “now anointed in Washington’s strategic thinking and official policy as citizens of a Cold War ally in Asia.”[5] It was at the first game of the tour, at Kōrakuen Stadium, that the Japanese national anthem was publicly broadcast for the first time since the end of the War. In all, the Seals played ten games in front of a cumulative audience of over 500,000 people.

I couldn’t find an image of Lefty O’Doul meeting Crown Prince Akihito, but this one features O’Doul shaking hands with sumo wrestler Maedayama Eigorō as Japanese baseball writer Sotaro Suzuki looks on. Accessed at http://www.prestigecollectiblesauction.com/site/images_items/Item_977_1.jpg

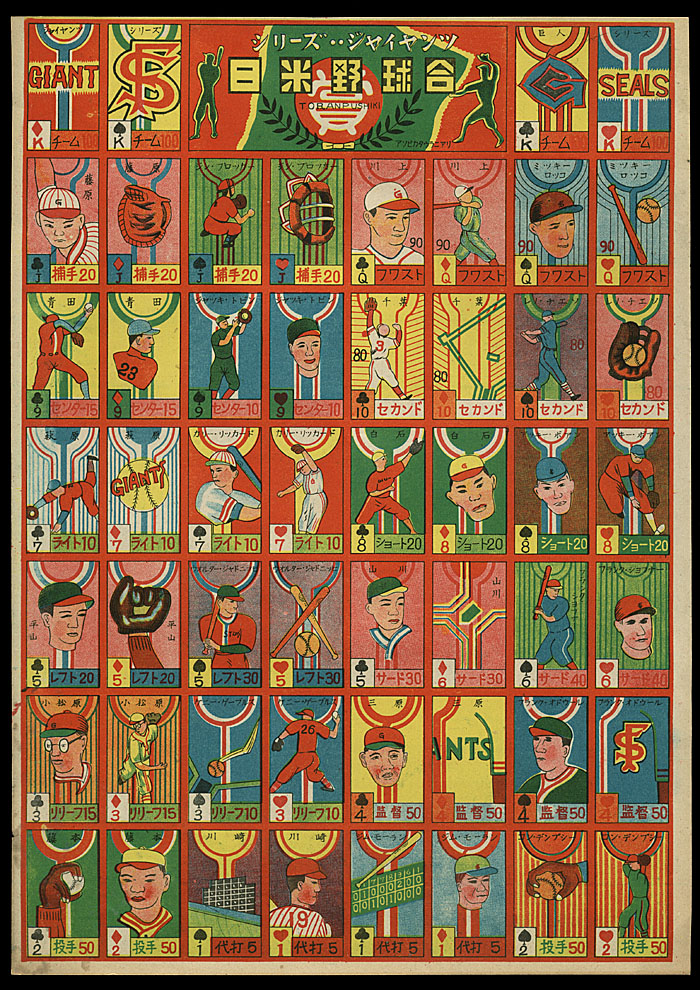

It was in the stands of the games of the tour that the Japanese public could experience good old American consumerism. Coca-cola, hot dogs, popcorn, and American cigarettes were available to Japanese citizens, at least those wealthy enough to pay the 300-yen ticket price and still have something left over for concessions, for the first time. The atmosphere at the ballparks demonstrated to the Japanese in attendance that the “benevolent American occupier and its favorite pastime brought to their country something more than peace, freedom, and democracy: it also brought the seductive appeal of the good life promised in those American creeds.”[6] In the fight against communism, spectatorship as well as the values of the game itself played an important role.

Set of commemorative playing cards featuring players from the San Francisco Seals and the Yomiuri Giants. One of the first post-War artifacts hinting at the capitalist potential of baseball in Japan. Image accessed at http://www.prestigecollectiblesauction.com/site/bid/bidplace.asp?itemid=3909

Thus, we can begin to see how people like MacArthur saw ways to use baseball as a weapon in the fight against communism overseas. The game was also, however, intertwined domestically in the Red Scare. This is especially visible in Jackie Robinson’s HUAC testimony in the wake of breaking baseball’s color barrier and becoming the first African-American to play in Major League Baseball, the top professional baseball league in the country.

The campaign to allow African Americans into the MLB originally began with the Communist Party of the USA in the 1920’s. The Communist Party and Lester Rodney, a sportswriter for the Daily Worker, even lobbied the Pittsburgh Pirates to host a tryout in 1942 for an African-American player, Roy Campanella. Ever-conservative Major League officials, however, pressured Pirates owner William Benswanger to call off the tryout. Even so, Campanella openly acknowledged the support he received from Rodney and the Communist Party, noting that they “pounded hard and unceasingly against the color line in organized ball.”[7] As such, calls for integration, as well as just about any other form of dissent within baseball, was frowned upon during the Red Scare era.

Ironically, then, it was a staunch anti-communist, Branch Rickey, who signed Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Montreal minor league affiliate in 1945, and promoted him to the Major Leagues in 1947. Following the promotion, Rickey instructed Arthur Mann, a sportswriter and close friend, to publish an article denying any influence of the Communist Part on the promotion of Robinson.[8] The fact that Rickey felt the need to preemptively distance himself from communism demonstrates how thoroughly the Red Scare environment permeated baseball and the Major Leagues. No action, especially one as controversial as integration, was safe from placement within a Cold War framework. Along the same lines, it is probably not a coincidence that both Robinson and Larry Doby, the second African-American to play in the Major Leagues who debuted two months after Robinson, were military veterans, which added to their credibility as potential Major Leaguers in the Red Scare era.[9]

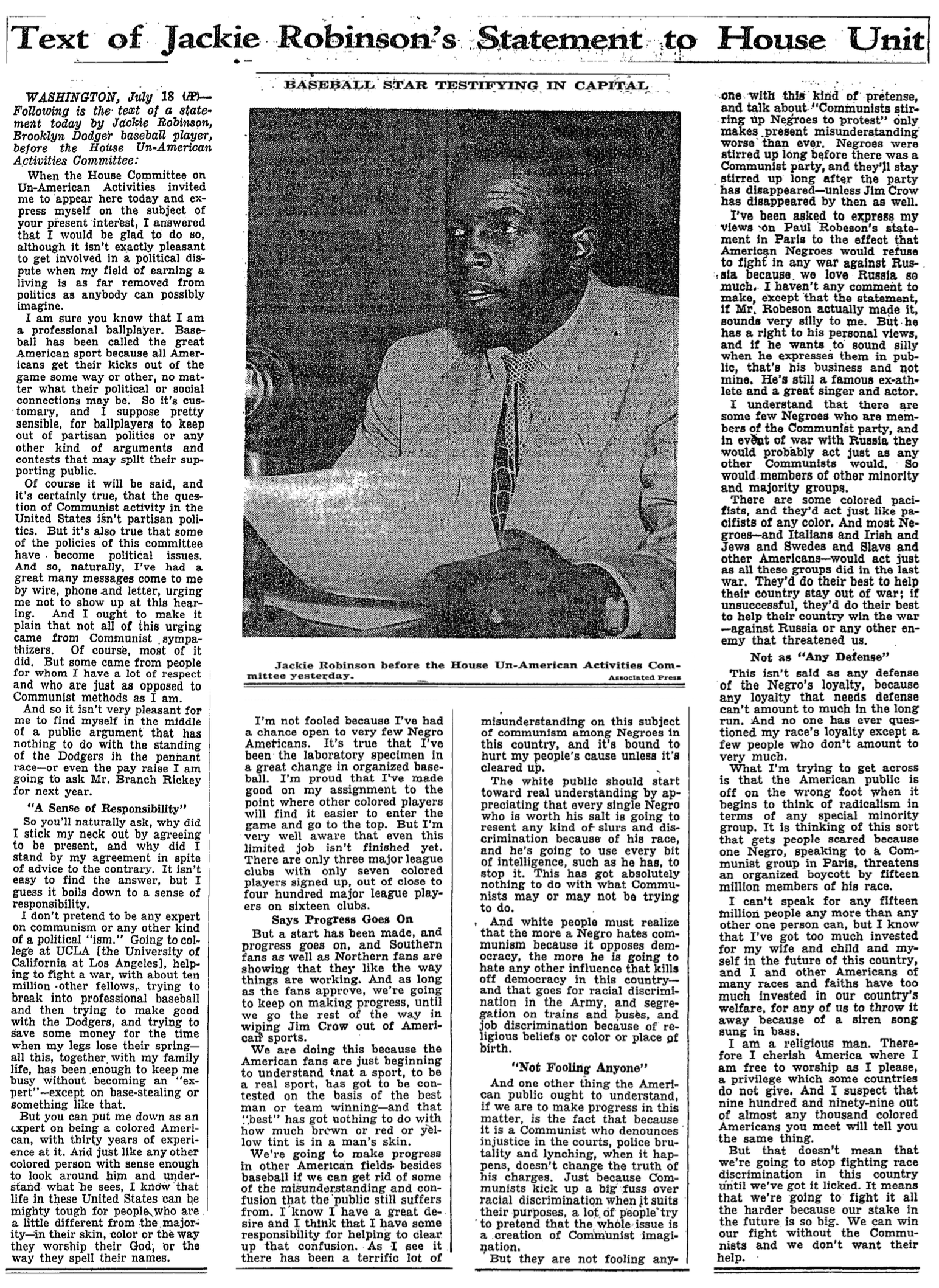

In 1949, a year after his debut in the Major Leagues, the House Un-American Activities Committee summoned Jackie Robinson to testify regarding comments made by Paul Robeson, an African-American singer and civil rights activist. Robeson had stated in April of that year that “it is unthinkable that American Negroes would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against a country [the USSR] which in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind.”[10] Robinson, for his part, was not obligated to testify before HUAC, and struggled with the decision of whether or not to do so. Fearing for his future as a baseball player, though, he decided to give a prepared statement. While most of Robinson’s testimony (which is included in full below) attempted to divert the focus from communism to Jim Crow and racial discrimination, he still felt the need to emphatically distance himself from communists by finishing his statement: “We can win our fight [against discrimination] without the Communists and we don’t want their help.”[11]

The New York Times included Robinson’s testimony in full the following day, and also included a front-page summary of his testimony. The article, written by C.P. Trussel, was careful to point out that Robinson was a “World War II veteran with thirty-one months’ service,” essentially portraying Robinson as the antithesis to Robeson’s earlier statement.[12] Though Jackie’s sentiments on integration and race relations might have been divisive in the climate of 1949, his take on communism served as a declaration from one of baseball’s most recognizable faces that, even if the league was taking the controversial stance of integration, it was a staunch supporter of democracy and American values in the internal struggle against communism during the Red Scare.

Thus, we can see in two seemingly unrelated stories––the San Francisco Seals’ 1949 tour of Japan and Jackie Robinson’s HUAC testimony a year after he broke professional baseball’s color barrier––a consistent narrative of baseball during the Cold War. Both internally in the United States and externally, across the Pacific Ocean, Americans used baseball as a tool for anticommunism. Whether encouraging international goodwill and finding allies in the international battle against communism, or distancing the position of black baseball players from more radical African-American voices, baseball and its imagery once again proved malleable enough to fit neatly into American ideals. This is not to say that baseball has inherent characteristics that somehow favor democracy over communism (or, for that matter, any of the other American values that sentimental writers have attached to baseball), but nevertheless its use and marketing in such a fashion by Americans like Douglas MacArthur, Lefty O’Doul, Branch Rickey, and Jackie Robinson is undeniable.

[1] Ron Briley, “Baseball and the Cold War: An Examination of Values,” OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 2, No. 1 (1986), 16. Accessed at http://jstor.org/stable/25162493

[2] Ron Briley, “Baseball and American Cultural Values,” OAH Magazine of History, Vol 7., No. 1 (1992), 61. Accessed at http://jstor.org/stable/25162858

[3] Briley, “Baseball and the Cold War,” 16.

[4] Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu, Transpacific Field of Dreams: How Baseball Linked the United States and Japan in Peace and War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 219.

[5] Ibid., 220.

[6] Ibid., 222.

[7] Robert Elias, The Empire Strikes Out: How Baseball Sold U.S. Foreign Policy and Promoted the American Way Abroad (New York: New Press, 2010), 163-64.

[8] Tom Gallagher, “Lester Rodney, the Daily Worker, and the Integration of Baseball,” National Pastime, vol. 19 (1999), 80.

[9] Elias, Empire Strikes Out, 223.

[10] Ronald A. Smith, “The Paul Robeson–Jackie Robinson Saga and a Political Collision,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 6, No. 2 (1979), 6.

[11] “Text of Jackie Robinson’s Statement to House Unit,” New York Times, July 19, 1949, 14. Accessed at http://search.proquest.com.proxybz.lib.montana.edu/docview/105816731?accountid=28148

[12] C.P. Trussel, “Jackie Robinson Terms Stand of Robeson on Negroes False,” New York Times, July 19, 1949, 1. Acessed at http://search.proquest.com.proxybz.lib.montana.edu/docview/105815174?accountid=28148