Back before I came out to MSU I used to do game testing. The work was all done through a third party company, so I had the opportunity to play a number of different types of games from different developers and publishers. Often these games would be in a very unfinished state, lacking final animations and textures, and often being voiced exclusively by Microsoft Sam. Seeing games like this, in such a bare but mechanically functional state, gives perspective on how games are build and just how similar many titles are.

A hallway is a bridge. When you think about it, there is, when you are playing a game, very little that separates the two. Each space is a corridor that you walk down. The only real difference is what bounds you in. With a hall, you are constrained by walls, where as on a bridge you are controlled by the absence of space. While it is true that there are different kinds of encounters that can be crafted for each space, it tends to be somewhat tricky to have an encounter with an attack helicopter in a closed hall, the way you navigate them is fundamentally the same. The two different spaces are palette swaps.

Playing those pre-release games made me realize just how much of gaming relies on visual cues and design to involve the player. Games that are mechanically similar can have their levels exchanged with little issue. An environment from Gears of War can function in Mass Effect, as they are both cover based shooters. It is the style that sets them apart, not their function. A shiny sci fi alien would be very out of place in the crumbling halls of the Gears world.

Note the waist high cover.

Similar cover system here too.

Even within the same game world, different environments can be combined in different ways to create unique settings. There is nothing mechanically different about the places created with different design pallets or “sets” but instead they rely on their visual distinction to create a new experience. Skyrim designers Joel Burgess and Nate Purkeypile addressed this at GDC 2013, citing an idea called “art fatigue.” They discuss how areas that are mechanically the same can, through visual differentiation, become interesting again.

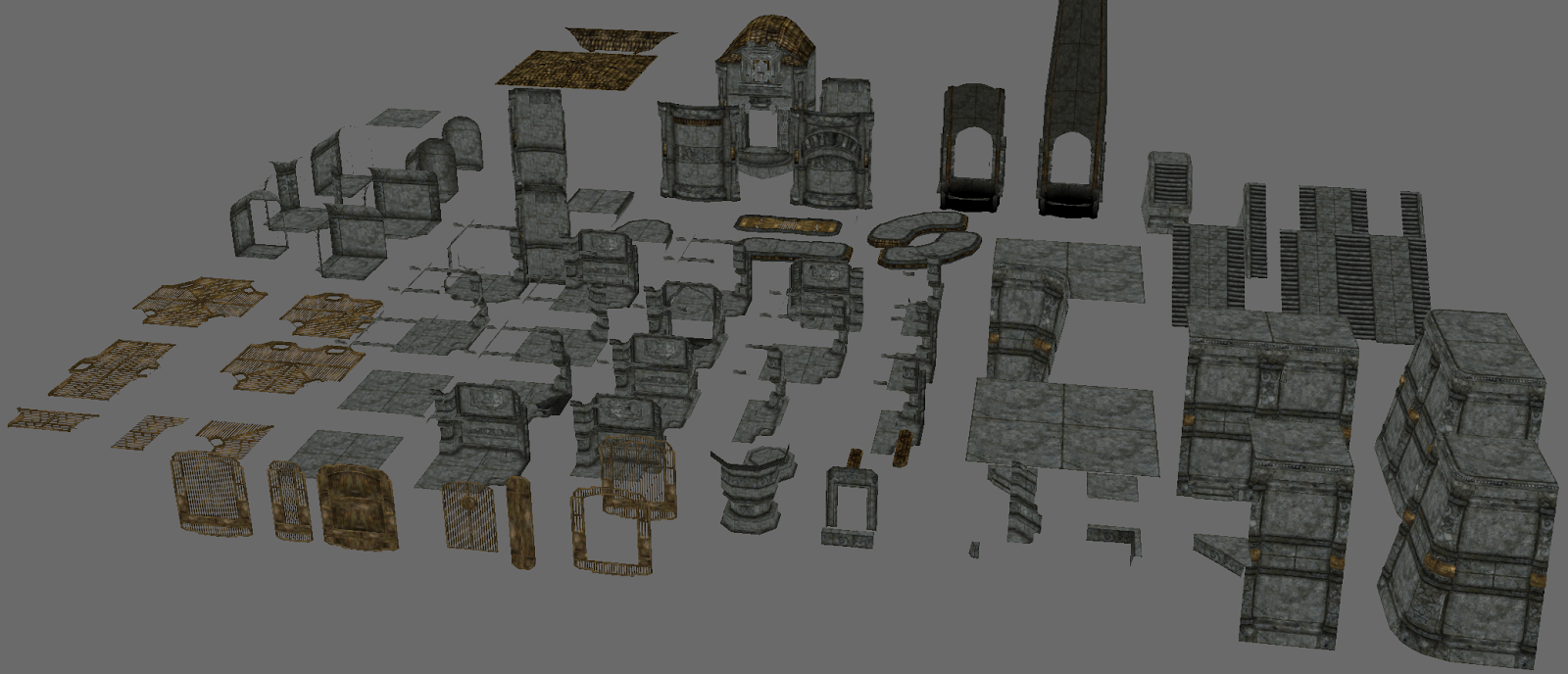

Skyrim is built using a series of “sets” or interlocking pieces that make up the level. Each set is a specific design, with the individual pieces combining to form rooms, halls and any other architectural features that the game might call for. Each set is made up of unique pieces, but each set contains similar parts. The sets are, in effect, palette swaps that are used to make up the fabric of the game. The designers use these different palettes to add variety to the game in an effort to avoid art fatigue.

All of these…

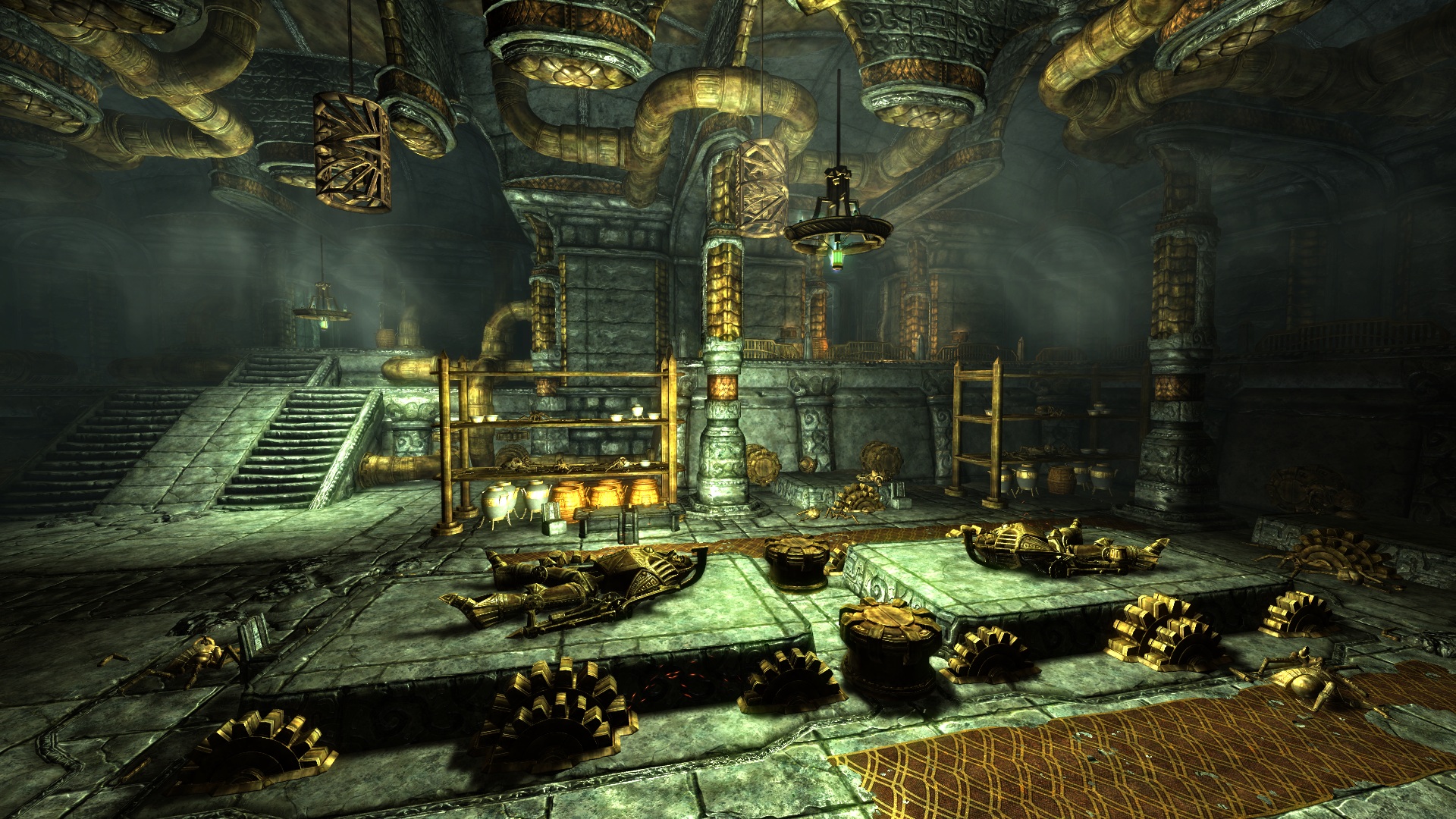

Go into making this.

Skyrim has two interesting cases regarding palette swaps that come from its use of art sets. The first is discussed in the article by Burgess and Purkeypile and is the idea of combining palettes. When designing the game before Skyrim, the level developers would often use the different sets in isolation, which created repeating architectural features between dungeons, rapidly leading to art fatigue. This was countered in Skyrim though blending sets. In the article, Burgess talks about using a type of fortress dungeon combined with an ice cave to create a unique setting. While mechanically identical to any other dungeon, it still retains the sense of being a new place, leading to feelings of discovery in the player.

The second case is when the palette is subsequently used to communicate the design or mechanics of an area. That same dungeon set used in collaboration with the ice cave was given a place in the lore of the game that revolved around mechanical creatures, traps and devices. The lore associated with the set and associated dungeons leads to a player expectation of encountering obstacles and enemies that are unique to that area, in this case coming in the form of mechanical enemies and hidden traps. While other areas of the game have other similar traps and opponents, the specific types, each with their own mechanism of disarming or countering through combat, usually only exist here.

This idea of telegraphing mechanics brings the concept of a palette swap full circle. Initially, palette swaps were designed to lighten the workload, both artistically and from a design perspective. Now, new sets are both artistically unique, with each one taking just as many man hours to create as the last, as well as informing the design. What started as a time saving mechanism has evolved into a method for diversifying art while normalizing mechanics before finally informing the mechanics of a space. Each aspect of design informs the others.