No Picnic on Mount Kenya gives an interesting account of life in a POW camp during World War Two. Unlike Seven Years in Tibet, the author is on an express adventure to climb, not to escape. The story embodies notions of heroism that we have discussed in class, as it depicts three men off on a daring adventure to climb a perilous mountain. For starters, this requires breaking out of the POW camp, which from past reading experience is not as hard as one would imagine. However, “As a matter of fact of all those who attempted to escape during our five years of captivity in order to reach Portuguese East Africa, only a group of four officers succeeded.” (23)

After the group of three escapes from the camp, they are in constant danger of being spotted by locals who could hand them over to the authorities. The duck through farms and forests, hop a train, and hide behind a cow before they even get to the base of the mountain. The book is not disaster porn or even highly dramatized. It does not follow many of the same narratives that we have talked about in class, but it does provide some historical perspective. The book contains many resemblances to Seven Years in Tibet, but not as much historical insight.

Unlike Seven Years in Tibet, it was a much harder trek to the base of the mountain(s) than Harrier had to experience. Yes Harrier had to trek through dense brush, evade inhabitants and wild animals (as did Giuan, Enzo, and Felice), but he was able to rapidly circumnavigate these obstacles. Felice encountered rhinoceroses and leopards.

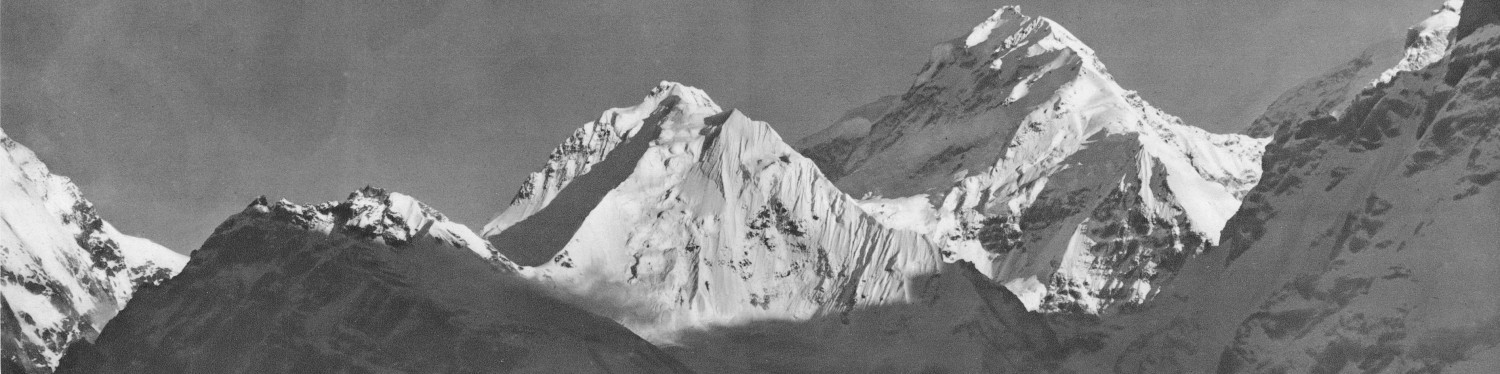

The book takes a large historical explanation of the mountain, and of mountaineering in general. Here the author posits the mountaineering aspect of their adventure. In the beginning, it was just a means to break from the monotony of everyday life in the POW camp. Life there consisted of smoking cigarettes, smoking more cigarettes, and occasionally smoking cigarettes. As the author realized that their climb had some historical significance to it, he goes into detail about previous mountaineering exploits, and where there adventure falls into that dialogue. They had no idea the scope of difficulty they were embarking on, indeed that it matched up to previous exploits by other famous mountaineers. “Never, I imagin, have mountaineers approached the mountain of their dreams- a colossus of 17,00 feet at that… Our ignorance proved an insuperable handicap from the poit of view of material achievment; but from the spiritual point of view, which is of far greater importance to the true mountaineer, it was in the nature of a gift from God.”

Only about halfway into the book do the characters begin the accent of the actual mountain. I have not read much by other Italian writers, but his style reminded me of Mount Analogue, in which the author went to great length to create the artistic and aesthetic side of the mountain. “I could not help recalling the what I had read about the master-pieces of the wise gardeners of China, said to have been experts at making miniature wonder-gardens.” (164)

It is interesting to note the good naturedness of the climbers. Even as they are returning back to their POW camp, they feel reinvigorated with the adventure that they succeeded in. It was a remarkable story of adventure in the face of adversity, in way that allowed the climbers to unlock their freedom in a philosophical way.