The ideas put forth in both of the readings for this week are a lot to bite off. Though there are some difficult concepts in these writings, I believe there are a couple of key ideas to take away and consider in mountaineering.

The first idea I want to discuss is one that Slemon writes about in “Postcolonialism in the Culture of Ascent.” Towards the end of this article Slemon writes, “it is impossible for mountaineering literature to ground a critique of present (neo-colonial) climbing practices on Everest without drawing on the discourse of classic mountaineering: to critique the present is implicitly endorse the imperial allegory of Everest’s colonial past.” (p. 63) What I think Slemon is arguing is that there is only so much of a lens through which we can look at mountaineering. Because of this, if one were to critique mountaineering now, the only other form of mountaineering that someone could look at would be that during the colonial era. The implication of that would be that of an implicit approval of colonial mountaineering, and all that came with that, which Slemon includes would be “a discourse of ‘Western’ prerogative, of border patrolling, of exclusivist professionalism and the grand narrative of imperial meanings.” (p. 63) It definitely becomes difficult to critique modern postcolonial mountaineering then, as the only form of mountaineering that can be approved of would be that of the colonial era. This is a difficult idea that is put forth, because the question has to be asked then, is there any way to critique anything really, without then implicitly giving approval to a function of the past?

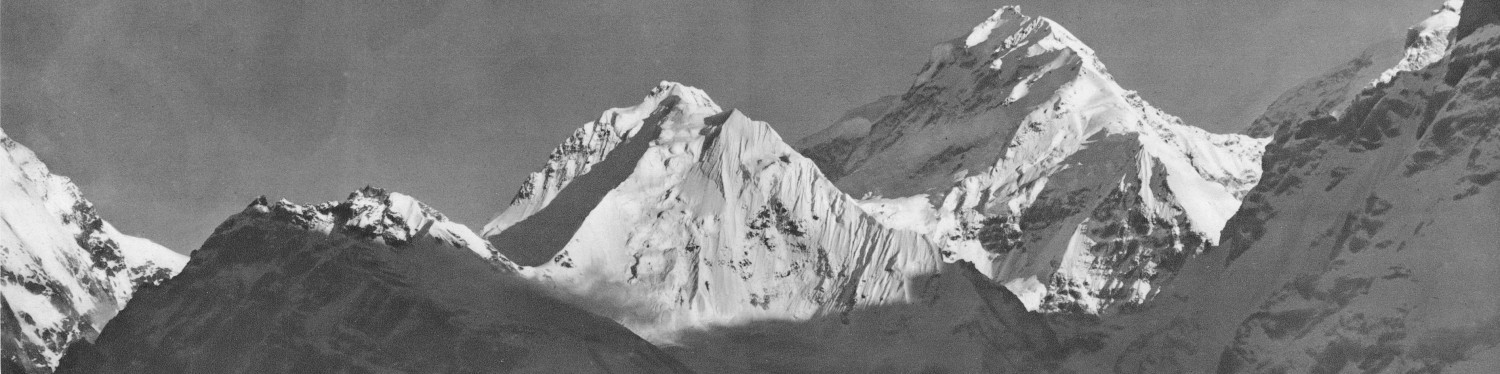

Edward Said’s Orientalism also presents some key concepts that must be considered in the history of mountaineering. Mainly, what we see in Orientalism is the kind of rhetoric and understanding that was brought to the Himalaya region as Westerners began to explore and climb the mountains, beginning in the colonial period. Said’s work, I think, really helps to give understanding to how native people of the Himalaya, the Nepali and Tibetan people, were viewed. Said shows us the lens that was at work this time, as this region was very much in the Orient. Since this was the case, places like India, Nepal, and Tibet would fit into the Oriental inferiority that Said says was the basis of Western thinking of the non-Western world (Said, p. 42). These areas that the Himalaya mountain range encompassed would be group together with the Oriental world and because of that, during much of mountaineering’s history, there would seemingly be no real reason for anthropological and enthnographic studies, as these areas were already “known” to the Western world. Along with that, I believe some of these elements of Orientalism are still seen today. This is especially true with the Sherpa people, and the huge lack of effort on the part of many to actually learn much of these people as a whole, and rather just lump them into a simplistic understanding that gives no credit to the richness of their culture and history.