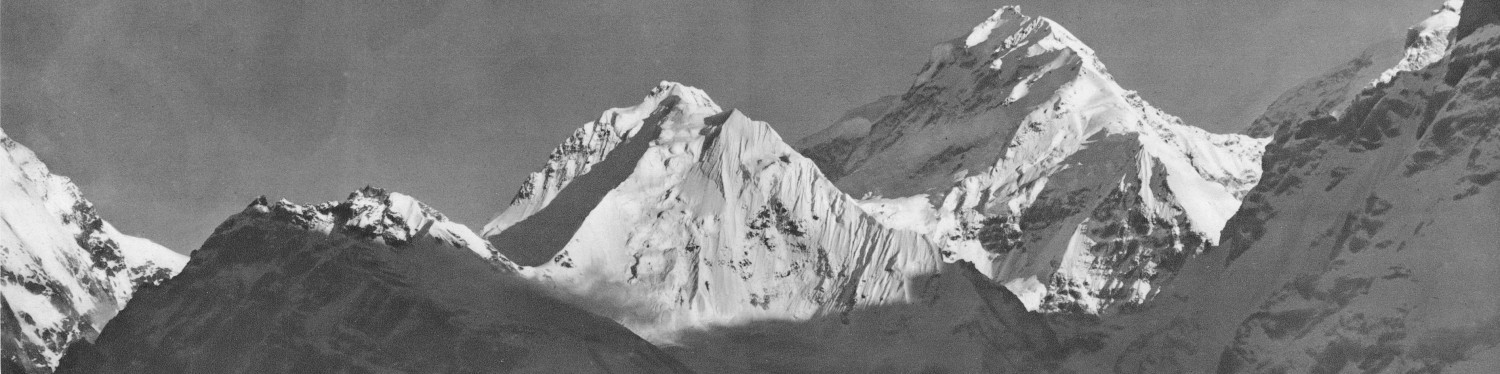

The Golden Age of Mountaineering seems to be a large theme in the readings for this week, so that is something to really hit on and look at. The first step is to ask, what is the Golden Age of Mountaineering, and from the readings, it seems to be the the post-war period when the 8,000 meter peaks in the Himalaya were being climbed. So basically, high-alpine mountain climbing during the 1950’s. And that definitely has much included in it, the first ascent of Everest as probably the most famous of successful summit attempts during this era, along with Annapurna, the first 8,000 meter peak climbed, and another very famous successful summit bid. I think the article “Social Climbing on Annapurna” does well to hit on the rhetoric of nationalism that so pervaded this time period, in the article, Julie Rak notes, “But, in Europe, national achievement became more essential than imperial achievement for mountaineers after World War II. For countries like France, Germany, and Japan which were conquered or defeated during the war, high-altitude mountaineering was a symbolic way for men… to regain respect for their nations,” (“Social Climbing on Annapurna”, 114). This seems to have been a huge part of mountaineering during this time. Nations, both those who suffered perhaps some kind of humiliation, and those who were weakened during the war, were able to in some sense prove the abilities of the nation. Great Britain climbed Everest, Italians summited K2, Germans climbed Nanga Parbat, among other conquered summits. This nationalism is perhaps best seen in debate about who summited Everest first, Hillary, a citizen of the British Commonwealth of New Zealand, or Norgay, who had ties with Tibet, Nepal, and India. This would become very important to some nationalists to have the claim of the first person to climb Everest, even to the point of disregarding the teamwork necessary in climbing.

It is also interesting to look at the treatment of Sherpas, and how they were viewed by European climbers who were employing the Sherpas for expeditions. Definitely, the rhetoric is there that the Sherpas were viewed as a far more uncivilized people than Europeans. Betsey Cowles comment on Sherpas, while on an expedition to Everest, point to this kind of thinking, “As I write, the Sherpas are cutting up like kids after school… Such laughter and gaiety! They are the dearest, most frolicsome people. (I intend to be as Sherpish as possible in the future.)” (Fallen Giants, 261). It does not necessarily appear that this is viewed purposefully as if the Sherpa people have less value than Europeans, but that they just are not as civilized. These also seems to come across in Herzog’s account of climbing Annapurna, where he, I think, makes the case that the Sherpas do not fully understand or are capable of as much as the Europeans, except as porters. Although, I would add that he does seem to change his view of Sherpas after all of the efforts they put into carrying down Herzog and Lachenal off the mountain, bringing them to safety. I believe this runs well into the nationalistic thinking of the time, as mountaineers were seeking to bolster the opinions of only there countries, so making Sherpas valued less than the Europeans would fit well into that rhetoric.