Mountains of the Mind is to say well titled, it chronicles the history of Eurocentric views towards mountains and perhaps more appropriate, it was to me at least, a very difficult book to work through. I found Macfarlane’s metaphors very dramatic and out of place in a nonfiction work; and it seemed to me he was trying to make mountains epic by comparing them to epics. Throughout the book there are references and metaphors to Star Trek, the Chronicles of Narnia and even a quote from the great J.R.R. Tolkien himself (page 262). This is not really necessary as mountains do not need any help being epic they in and of themselves are epic in nature without comparing them to works of fiction.

I do have a qualm though, it seems of all the writers, adventures and poets that Macfarlane touches he leaves out one of the most important. He mentions Tolkien only in one sentence and only to propel his own metaphor. Who is Tolkien if not the master of mountains? Tolkien’s great opus is centered around mountains: in The Hobbit they journey over the perilous Misty Mountains only to go to their intended destination of the Lonely Mountain. The Lonely Mountain represents so much; populated by evil incarnate the dragon Smaug, on the ruins of the late prosperous Dwarvian kingdom. Then in The Lord of the Rings the Misty Mountains are traversed again this time in pursuit to Mount Doom to destroy the powerful One Ring. These are truly mountains of the mind if any ever existed.

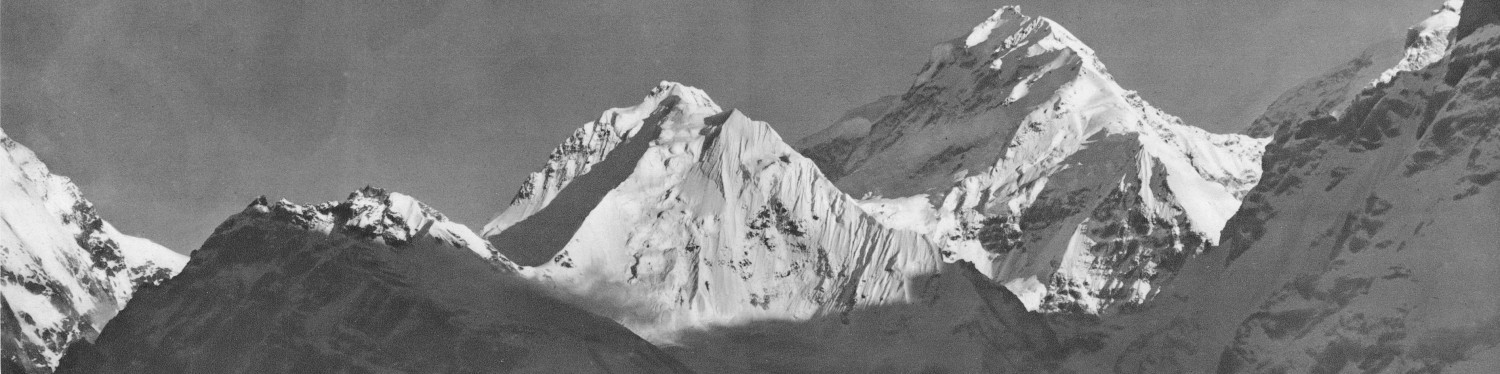

Once sifting through the metaphors and Macfarlane’s own mountain journeys, there are some points that are actually interesting. The chronicle of how mountains have been viewed in the past by humans (again from a predominately European perspective, and even then mostly English) from hostile territory characterized by mythical animals drawn into the blank areas on maps to the formidable challenge and serene beauty they were popularly transformed into. The image of mountain being a serene scene of beauty has always been engraved in my mind and it was difficult to believe that there was a time that this was not the case.

“Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory” on the other painted a more literary picture. It had never occurred to me the depth in which English poets are fixated on flowers and gardens and never invoke or completely ignore something as iconic as the image of a mountain. I felt wanting in the article however, it cut off the history and evolution of mountains in poetry and literature far too early to truly show the evolution of an idea. I was surprised to see Petrarch mentioned – it is very abnormal to see him mentioned and not coupled with the unobtainable Lady Laura, and of all things in the universe he was talking about mountains. Not only does this leap far out of time when mountains were still somewhat mythical but it is by and far an unusual subject for Petrarch’s pen.

“Imperial Eyes” I thought was sort of misplaced among the readings. It mentions the idea of surveying and exploration turning inward in an increasing imperialistic contest but does not actually touch on the subject of mountains themselves as an Imperial Point. I also found it odd to that Linnaeus was included in this article, his realm being more biological then geographical. While I understood the contents of the article it is a stretch in my mind to see how it fits in with the rest of this week’s readings, and hopefully with this week’s seminar I can become enlightened.